1. Introduction

In the past few years I have had the opportunity to teach composition at a diverse series of Colleges and Universities, public and private, on both the East and West Coast. My experiences with graduate and undergraduate students has led me to realize that contemporary composition pedagogy in America is based on a number of fundamental misunderstandings that undermine its effectiveness for preparing the next generation of artists.

With the exception of tacked-on courses in ethnomusicology or technology, many music curriculæ have remained unchanged for nearly a century. The basic assumption that students arrive prepared with some practical background in classical repertoire is, in my experience, false. However, this outdated assumption leads to the extensive teaching of “Common Practice” music theory, which proves elusive to students unfamiliar with the music. When asked to compose, students have been given a set of theoretical tools that have little to do with the music they listen to on their own — the music they hear in their minds. Since most contemporary music is produced and reproduced through digital technology, an adequate curriculum must deal thoroughly with contemporary technology. The same technology has challenged, and often replaced, live performance. Performance in the 21st Century can be infused with an urgency that differentiates it from recorded media, but only by musicians who have studied both mechanical and æsthetic aspects of music as a performative art.

It is past time for teachers of composition to examine the musical environment in which they live, and compare it to the skills they are passing along to their students. An honest evaluation would detect significant discrepancies. We should be asking ourselves two questions: “What do my students know before they come to me?” and “What does a 21st century composer need to know?” From there, we can begin to formulate a pedagogical approach for the current generation of students.

2. Repertoire

It would seem that the ideal university music student would be a member of a 19th Century bourgeois family who had a piano in their parlor and the socioeconomic means to attend orchestral and operatic performances. This student would have good keyboard skills, and have played or heard a great deal of 18th and 19th Century music. Whether or not a classroom full of such students has ever existed, I have never seen one. In every institution I have been a part of, eventually I hear that “students don’t know any music.”

Unfortunately, there is a genuine problem here to which teachers of composition must adapt. Music is not offered at many secondary schools. Passive listening to recordings, radio or television has almost entirely displaced amateur music-making, resulting in a body of students who are substantially less literate in standard repertoire. Whereas historically it would have been unthinkable for a student to study music without substantial previous experience, I have recently had students who neither play an instrument nor sing.

One obvious reaction to the situation is to place incoming students on a remedial listening program and to take more time in class to play music. While I believe it is important to introduce students to great music, this approach can have undesirable results. Students learn to separate music they listen to for class, and music they enjoy. And an increased focus on the common practice period enforces a canon that excludes “electives” like ethnomusicology or technology.

Instead, contemporary curriculæ need to integrate common practice teaching into a broader view of music. Although 21st Century students do not know standard repertoire as well as past students, many of them have very broad and eclectic listening habits. Most professors know that classical music was strongly related to the popular and dance music of its day, but there is a great reluctance to deal with the popular music of our day. To those that find nothing of interest in contemporary popular music, I suggest listening to Radiohead, Aphex Twin, or the Nortec Collective. Contemporary electronia has a very complex timbral æsthetic, even if it is organized around a simple basic rhythm. American Music is inherently multicultural, students have been inundated by it for most of their lives, and teachers are missing a great opportunity if they choose to ignore this body of knowledge.

It is also worthwhile to question the premise that 20th Century music is less “accessible” than earlier work. “Music Post-1945” does not need to be presented as an elective or upper division class. There is much to be said about starting with music that comes from the students’ lifetime; music written by living composers speaks to contemporary experience. I have experienced classes of non-music majors who were very excited by the music of Heiner Gobbels, Louis Andriessen, and Steve Reich. (Oddly, music majors were very antagonistic towards the same music.) Connecting contemporary compositional techniques to that of the medieval and renaissance periods is often fruitful, another reason to break the hegemony of the common practice.

3. Theory

Broadening the repertoire to include jazz, popular music and non-European music must have a direct effect on the perception of music theory. For approximately two hundred years, Europeans produced music that was organized around harmonic function. This is a relatively small part of musical practice as a whole, yet it has become the gospel for musical instruction. Students begin with Bach, a composer who comes from a completely different world and whose unique genius makes his practice almost completely inaccessible. In a few terms we can barely get beyond teaching the rules, which is just the surface of writing in the style of Bach.

Bach was better known in his lifetime as an improviser, but that aspect of his career has become a footnote to the study of his compositions. Although most “great” composers improvised, the music that was not written down has past; without a documented tradition, improvised music has not generated any music theory and has become invisible in a traditional curriculum. It is unfortunate that contemporary composition students are not asked to improvise. In the 21st Century, recordings and subsequent transcriptions have provided us with ample opportunity to theorize and teach improvised and vernacular music in the classroom.

Fitting a series of music theory courses into a four-year degree is a constant problem. Choosing to major in music after the sophomore year might be awkward or impossible. Therefore, it is inevitable that new topics will displace others. While common practice offers a compelling tonal narrative that moves from the diatonic to the chromatic, preserving that narrative forces a set of topics whose musical relevance is relatively small. For instance, the textbook I have recently used devotes two chapters to Augmented Sixth Chords. Even in Romantic Music, this chord is very rare. And while I enjoy the sonority, I cannot justify spending very much time on it. Even after long explanation, I find that most students use these harmonies inappropriately because they do not situate its function in the context of a larger musical style.

Music theory should address basic principals that encompass multiple musical practices. A course on melodies could include Josquin de Prez, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Billie Holiday. Rhythm and polyrhythm, subjects that are hardly taught in tradition music theory, would range from Max Roach to Gamelan to Cooper and Meyers. Other subjects could include timbre, harmonic function, text setting, and large-scale form. A truly contemporary approach to theory and composition would encompass as much wonderful music as possible. Rather than presenting the students a set of tools limited to harmonic function and rhetorical form, they would be given a large range of tools to help them craft their own musical expression. As a professor, I have been somewhat self-conscious about bringing my own music to class, because students quickly realize it has, at best, a tangential relationship to common practice. Wouldn’t it be better for composers to teach theories that they actually use?

4. Technology

Music has always been at the cutting edge of technology. From bone flutes of 4000 BC to the Baroque pipe organ to the development of the piano during the industrial revolution, human beings have always used the most sophisticated craft available to fashion musical instruments. From this perspective, the fact that music pedagogy stops at pre-World War I technology (except, perhaps, for an elective course in “music technology”) is an historical deviation that is made especially jarring by the dominance of recording technology in 21st Century musical experience.

One only has to consider the all the music we have heard. What percentage is live? Even in a live situation, recorded music has changed the way an audience perceives the sound and influenced the measure of a “good” performance. When digital editing can create the illusion a “perfect” performance, musicians feel driven to live up to that illusion on stage. Similarly, a composer’s body of work exists primarily in documentary recordings. Without a basic knowledge of how to get a good recording, young composers are at a serious disadvantage when managing their careers.

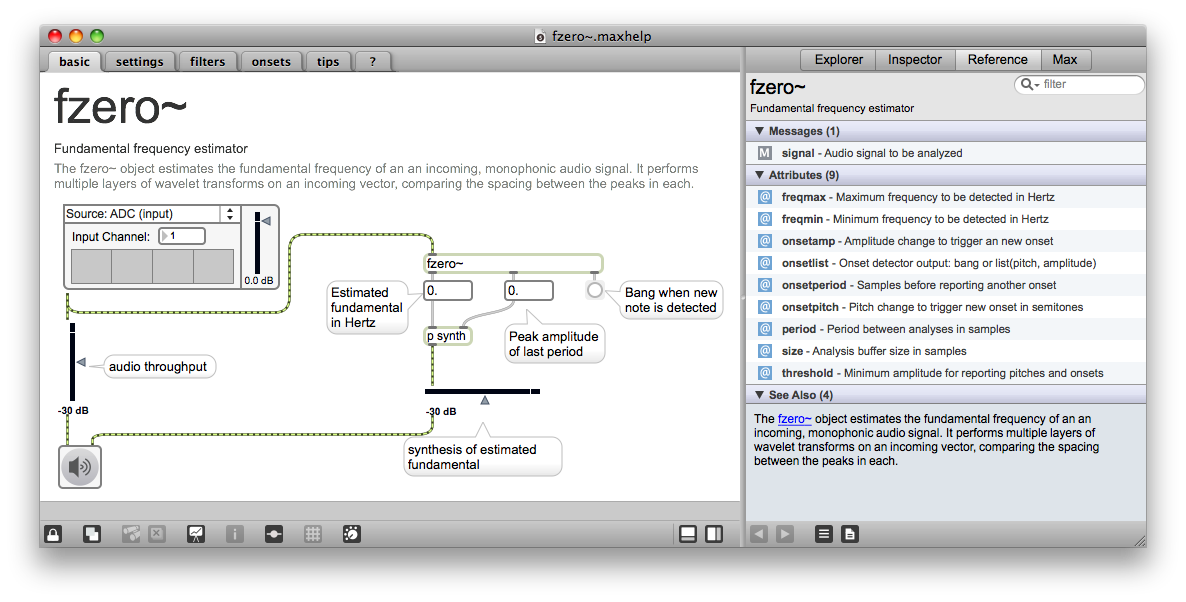

Taking a step beyond reproduction, composers need to be aware of the possible uses of computer technology in creation and performance of new compositions. Many successful composers use MIDI sequences at various points in the creative process. Initially, sequencers can be used to capture improvisations in a form that is easily edited and analyzed. Beginning students often have trouble remembering their ideas while they struggle to notate them. Learning to use a sequencer as a transcription assistant can be extremely helpful at this stage, especially if they are studying music theory that posits a continuum from improvisation to composition. As a piece grows, MIDI playback can provide students with a model of their work in progress. Even for students with strong keyboard skills, this type of model offers a valuable opportunity to hear a piece in tempo and with some semblance of timbral nuance. Obviously, a sequenced performance is not the same as a human performance, and we should be teaching our students the strengths and weaknesses of such compositional assistance. Care must also be taken to make sure that students use these tools while developing their ear. Often with the same software, composers can produce clearly engraved scores and parts. How music is presented to performers is critical, and should be taught as part of the entire process of composing.

Finally, young composers should work with electroacoustic media. A few seconds of popular radio or television can encompass a sonic universe of synthesized and processed sound. This is the environment in which we live. Electronic sound offers an incredible flexibility that can spark the creativity of any musician. Even if one chooses to write entirely for acoustic instruments, learning the process of digitally sculpting a sound or refining a generative algorithm will have profound æsthetic implications that develop the musical imagination.

5. Performance

As audiences become accustomed to recorded music, musicians must seriously consider the medium of live performance. Composers and performers must create an experience in concert that is uniquely live, that cannot be captured by recording. There must be a reason to hear music in concert.

Most curriculæ draw a sharp distinction between performers and composers, and neither group spends any time considering the musical performance as a theatrical experience. John Cage’s 4’33” is brought up as a curiosity, without realizing the message — that the frame is part of the art. While it might be charming to see undergraduates in mismatched blacks and white socks struggling to make a simple bow, they also indicate a failure in performance pedagogy. Teaching at a school of arts, I have seen young theater and dance students walk on stage with captivating poise. Music students would benefit from some brief contact with these arts.

Even though musical performers do not learn about staging, composers are taught to leave the realization of their music in the hands of these same performers. Contemporary composers who do not perform, conduct or improvise are at a real disadvantage when trying to help their music live. Even if composition students can learn to create acceptable parts and scores, they should realize that that is not the end of their job. More experienced composers understand the critical importance of successful rehearsal. I have performed interesting music that completely failed because the composer had no idea how that music would (or would not) come together in a human ensemble. And when the rehearsal started going badly, the composer would either sulk in a corner or get angry with the musicians. (I remember one particular rehearsal where this happened; the composer’s teacher was in attendance and did nothing.) Composers do not have to be virtuosic, but they must conduct and they must perform. Drama students are usually required to spend a number of hours as stagehands. They learn lighting, sound, stage managing, etc. I have been surprised at the number of composers who have no idea about any of these things, and have walked out of concerts when it takes a quarter of an hour to change the stage from a solo piano to a string quartet. Electronic technology amplifies complications in staging exponentially, not to mention the additional lifting and carrying. It would be luxurious if composers could ignore these aspects of the performance, but most of us do not have that choice. Young composers should be prepared to do what it takes to present their music.

The æsthetic of performance must also be taught. American music of the 1960’s understood itself as a performance art, at times to an absurd degree. More recently, Kronos Quartet did not become famous because of spotless execution, but because of the energy they brought to the stage. Students should study these examples and apply them to their work. Furthermore, the world of digital art is currently fascinated by multimedia works. Video technology is very similar to audio technology; a composer who uses Pro Tools will recognize the same keyboard shortcuts when they pick up Final Cut. A thorough examination of digital media is beyond the scope of a curriculum based on music, but students should have a foundation if they choose to explore that area on their own.

6. Conclusion

In the 20th Century, recording technology created a paradigm shift in the way that music is appreciated and the role music and musicians play in our culture. Teaching of music has adapted, from general music appreciation to specialized studies such as ethnomusicology. It is inevitable that contemporary technology will alter the teaching of music theory and composition, and that change is already happening. The question is not whether traditional pedagogy should be updated, but whether composers will participate in updating it, or continue to teach a body of knowledge that is increasingly obsolete. Music is written by those who participate.

Although this sounds radical, I also believe that change should be made deliberately and gradually. It is quite valuable that students and faculty across the country are speaking the same language when teaching music composition and theory. An academic career can span many institutions (as mine has), which would be problematized if each were teaching a unique set of musical ideas. (Of course, the realities of accreditation would prevent that from happening.) From traditional pedagogy, we inherit a clear and solid trajectory for developing musical understanding. While it is grounded in an anachronistic style, “common practice” theory can address fundamental issues of musicality if taught and learned in an open frame of mind. Many of the professors I have worked with are very capable at revealing the underlying principals behind initially esoteric concepts.

Another advantage of the current system is that historians, performers and composers all sit in the same classroom and learn the same theory. Composers should become closer to performers, but it is critical that the study of music remains connected. Under the duress of 20th Century æsthetics, Art History and Art Practice have separated into separate disciplines. Educators must not let that happen to music.

The development of compositional pedagogy must be gradual, but the shift in basic philosophy is overdue. Ethnomusicology, music technology, and conducting should not continue to be tangential to teaching composition; they should be integrated at all levels. Contemporary composition pedagogy is currently producing a generation of composers who are not connected to the contemporary world. That young composers continue to be successful is to their credit; good students can be expected to expand beyond their educational models. Having attended American Universities, many of us had to do the same thing when we were students. We should consider what we had to teach ourselves, and what is really basic to our musical lives — and let that influence our teaching.