2002, 21′ for violoncello and live electronics

First performance: April 2002, Smith Hall, Irvine

Commissioned and performed by Hugh Livingston, violoncello

Subsequent Performances: April 2002, EMF@ The Flea, New York September. 2005, Sacramento New Music Festival, Frances Marie Uitti.

The title, Daguerreotype, refers to one of the earliest photographic processes, first published by Daguerre of Paris in 1839, in which an image is formed on a silver plate sensitized by iodine and then developed by exposure to the vapor of mercury. I find portraits made with this process to be quite interesting, inhabiting a middle ground between painted portraits and contemporary photography. Because exposure times could be almost a minute, subjects hold very serious, composed postures that are quite different than a candid snapshot. Daguerreotypes are not fixed instants of time, but the result of a prolonged meditation that seems to dig deeper than a superficial glance. This is metaphorically related to composing music, especially composing a piece for a specific performer who is also an improvisor. Daguerreotype was composed in collaboration with cellist Hugh Livingston who, like all contemporary performers, has a specific vocabulary of techniques and expressive gestures. In the early stages of the composition, we discussed the physical experience of playing the cello – what was possible, what was challenging, what was rewarding for the player, and so forth. Taking this material back to my studio, I found myself engaging the qualitative difference between improvised and composed music (both of which are present here), and the performer’s role in bringing spontaneity to a pre-composed piece. I played the role of photographer composing a portrait of a cellist: my subject.

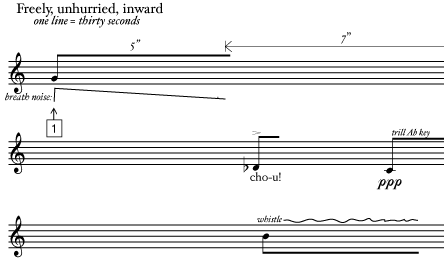

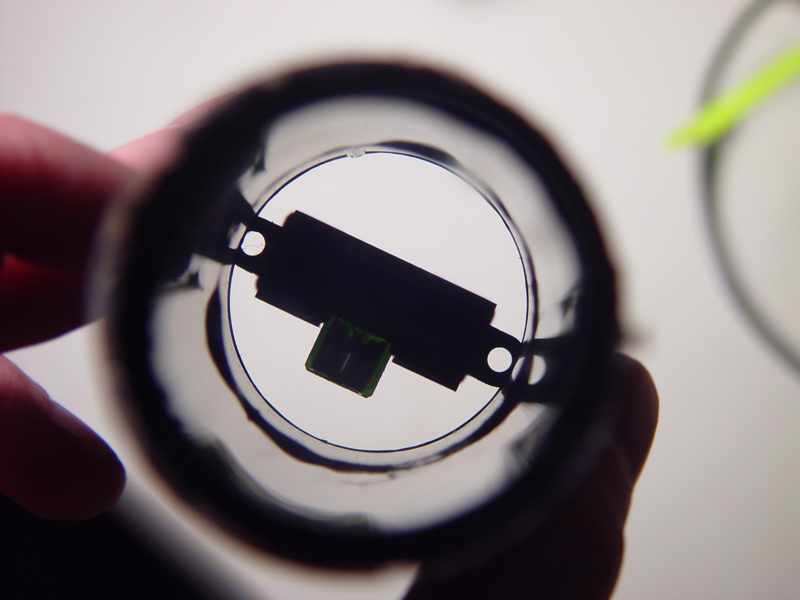

The live sound of the cello is electronically processed throughout the piece. The role of this processing is to act as an aural lens, focussing, refracting, and framing aspects of the original cello sound. Dr. Livingston is a student of Chinese music, which has inspired a plethora of pizzicato techniques — various ways of plucking the strings. The beginning section of my score features very specific ways and places for the player to pluck, and the subtle differences between these are enlarged by the electronic processing. For the most part, the electronics stay in this role of augmenting the subject. However, there is a significant moment around the half-way point where the electronic part presents a series of variations on a motif played by the cellist and “remembered” by the computer earlier in the piece. This allows space for the cellist to have an improvised duet with her own reflection. In other improvisational sections, the technology also acts like a photograph by assisting and shaping memory. Snapshots of previously performed gestures are presented in a new context, as if viewing them from a different angle.